By Meredith Thompson

This post originally appeared on TheHumanist.com.

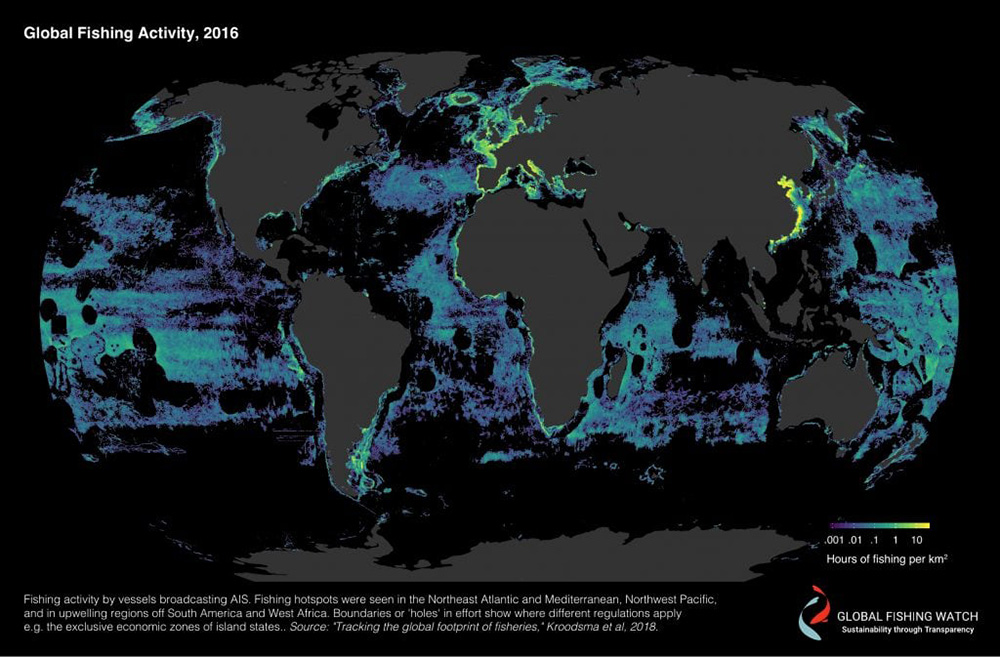

The commercial fishing industry is a multinational, multi-billion dollar operation that has been devastating our planet for decades. But its footprint has been difficult to follow, until now. Last week the journal Science published a study capturing the true extent of the environmental impact of industrial fishing. Alarmingly, researchers found that humans are fishing at least 55 percent of the world’s oceans.

Using satellite feeds and machine-learning techniques, researchers from the University of California Santa Barbara, Dalhousie University, Stanford University, National Geographic Pristine Seas, SkyTruth, and Global Fishing Watch, tapped into 22 billion signals from vessels at sea through automatic identification systems (AIS). AIS broadcasts the position, speed, and turning angle of ships to prevent collisions at sea. Thanks to Google and machine-learning algorithms, researchers were able to identify the characteristics of each vessel, including the type of fishing gear they were likely using. The findings are unprecedented and significant in that they quantified industrial fishing practices in a way that had never been done before, and the result shows the intensity of global fishing is far greater than anyone predicted.

But researchers expect that our impact is even greater still. Smaller fishing vessels are not required to have AIS, and the larger ones that do can switch off the tracker, or not have them installed at all to partake in illegal operations. Because of this, researchers estimate that the percentage of oceans fished could be as high as 73 percent.

Jackie Savitz, chief policy officer for the advocacy group Oceana told the Washington Post, “Fishing is happening almost everywhere and all the time. I think people don’t really have a sense of how heavily fished our oceans are and how intensely they are fished.” Humans, with our desire for the flesh of fishes, are putting great pressure on fish populations and straining our already fragile oceans. Scientists estimate that each year commercial fishing kills between 0.97 and 2.7 trillion fish worldwide, and that number, due to increasing human population and demand, is only increasing. But fish populations, unable to keep up with the rate at which we are killing them, are declining. Populations of fish who are among the most-consumed—tunas, flounders, cods, halibuts, and swordfishes—have plummeted by 90 percent since the 1950s, disrupting the health of aquatic ecosystems worldwide. The disappearance of these predatory fishes have radically altered ecological niches and wreaked havoc on ocean ecosystems as the number of prey animals increase. Furthermore, bycatch—unwanted animals caught unintentionally by indiscriminate fishing methods—kills billions of other animals each year. Scientists estimate that 650,000 whales, dolphins, and seals alone were killed each year throughout the 1990s as a result of bycatch.

Researchers involved in the study hope that their findings will provide transparency into the world of commercial fishing and promote sustainability measures like creating untouchable reserves or fish farming. But these alternatives fail in addressing the bigger issues, like the existence of the demand in the first place, and the effect it continues to have on fishes and ecosystems worldwide, regardless of “sustainability” efforts.

While fish farming has often been viewed as a solution to commercial fishing, it ignores the environmental hazards and questionable ethics associated with the practice. First off, a great number of fishes caught in the wild are required to feed fishes trapped in farms. It takes ten pounds of fish to create 2.2 pounds of fishmeal. Farms also severely damage the ecosystems where they are located. Since maximum production efficiency is about the only thing that matters to these operations, they densely pack fishes in pens. The accumulated feces and putrid living conditions deplete the water around farms of oxygen, and play host to numerous deadly parasites and viruses. Additionally, natural buffers like mangrove forests are often destroyed to make room for farming operations. Without a natural buffer between land and ocean, coastal animal (human and non-human) populations are more susceptible to devastation associated with natural disasters and erosion.

Now, more than ever, it is critical to examine our relationship with fish. Marine biologist Sylvia Earle told National Geographic in 2003, “I have heard that the record for a bluefin tuna, a 440-pound (200-kilogram) specimen, sold for $180,000. So this kind of exploitation is not for the starving millions, but driven by high-end appetites.” Earle, who received the American Humanist Association’s Isaac Asimov Science Award last year, went on to say:

Most people also don’t know how bad it is for us to be eating so much fish, not only because of the destruction of an ecosystem vital to survival but also because the big predatory fish are full of the toxins and other pollutants that we cast into the oceans. It’s not as healthy to eat fish as most people believe.

With all this evidence pointing at the devastation fishing causes not only to fish but to global ecosystems as well, why do we continue to support the industry? It’s so important that we take a step back from our practices and consider the moral implications of our relationship with fish. It’s too easy for us to forgo conversation on the individual lives of fishes, and for too long we have avoided it altogether. How unfortunate that we dismiss the varied and vast inhabitants of the ocean simply because it’s harder to understand them and because we’re used to a world that exploits them. Breakthroughs in ethology, sociobiology, neurobiology, and ecology have made it easier for us to understand their lives. As humanists, we must remain curious and open ourselves to learning more—for their sakes, for our sakes, and for our planet’s sake.